Open Mon - Fri 9:00 am – 4:00 pm, Sat & Sun Closed

.JPG)

.jpeg)

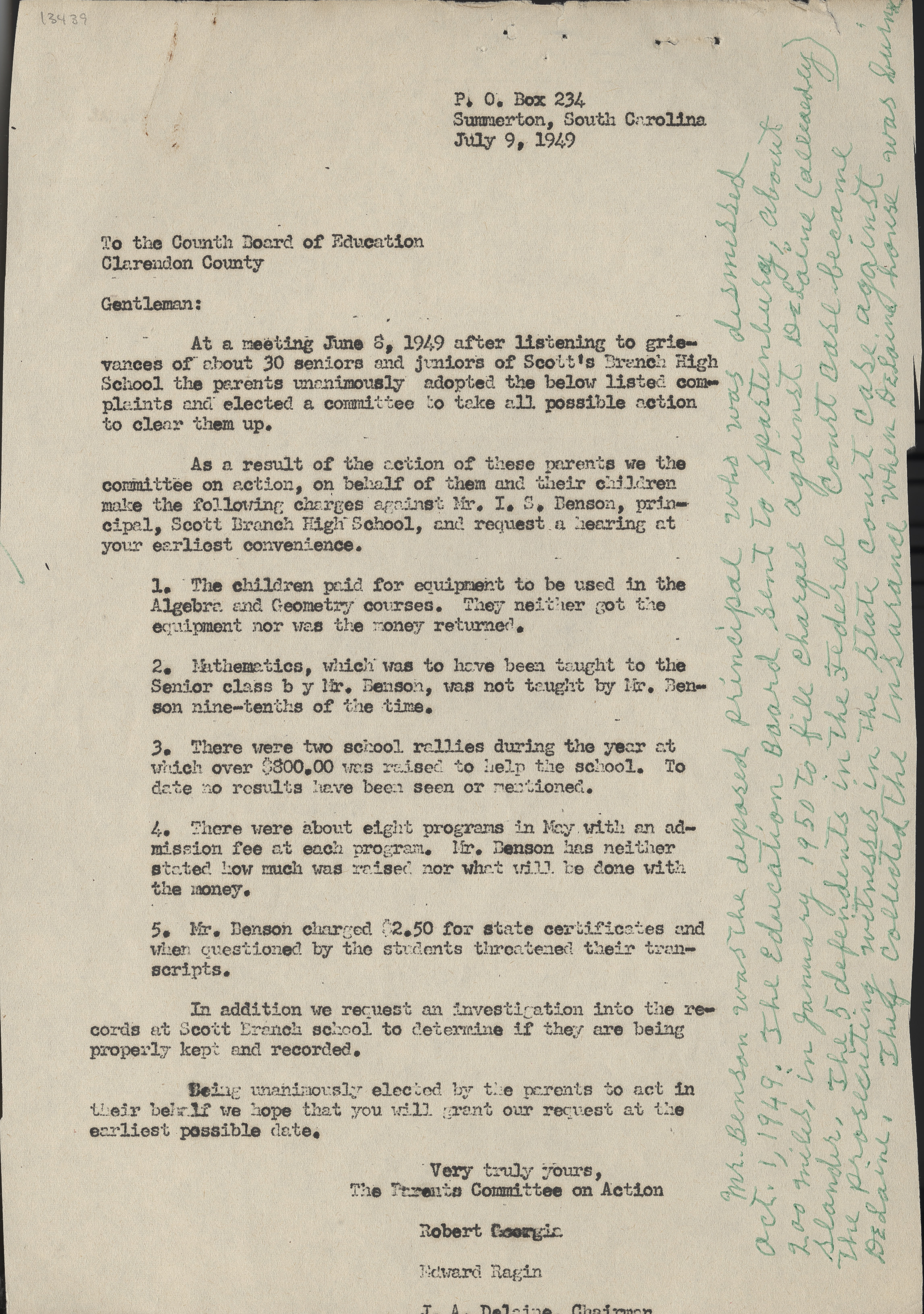

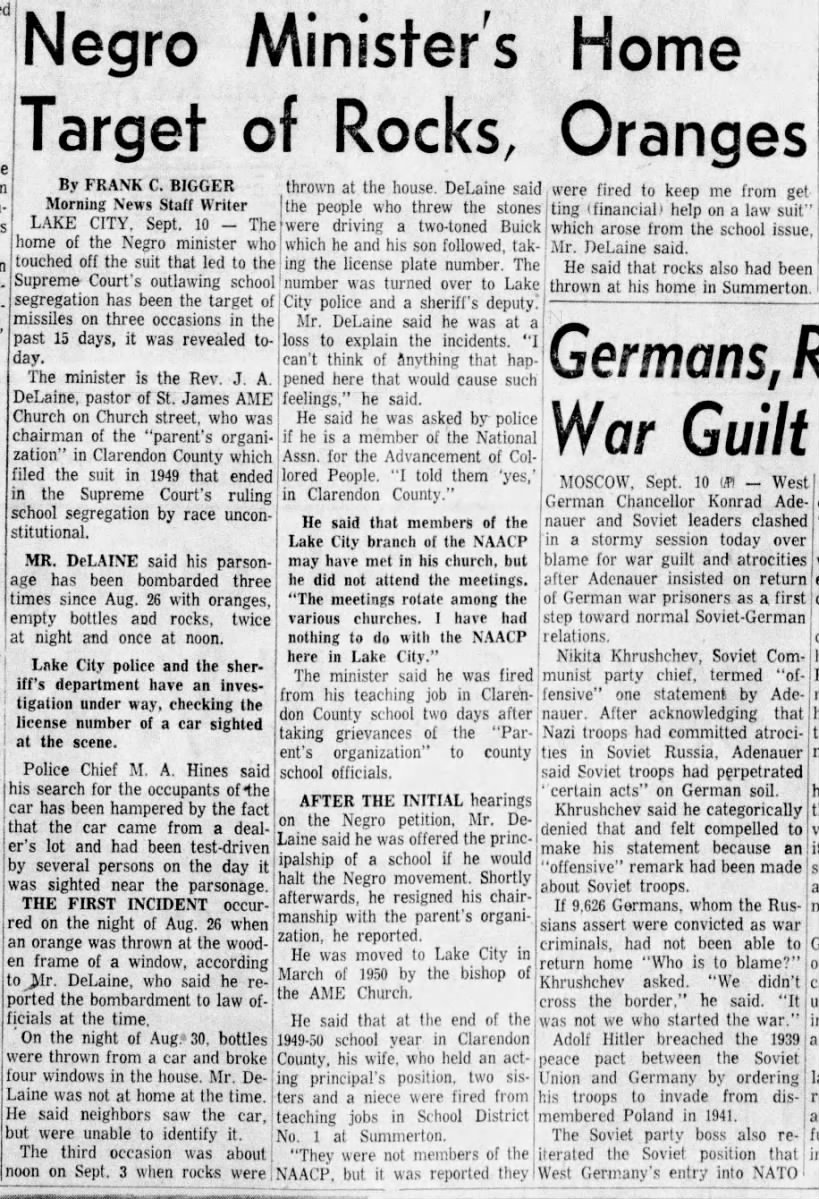

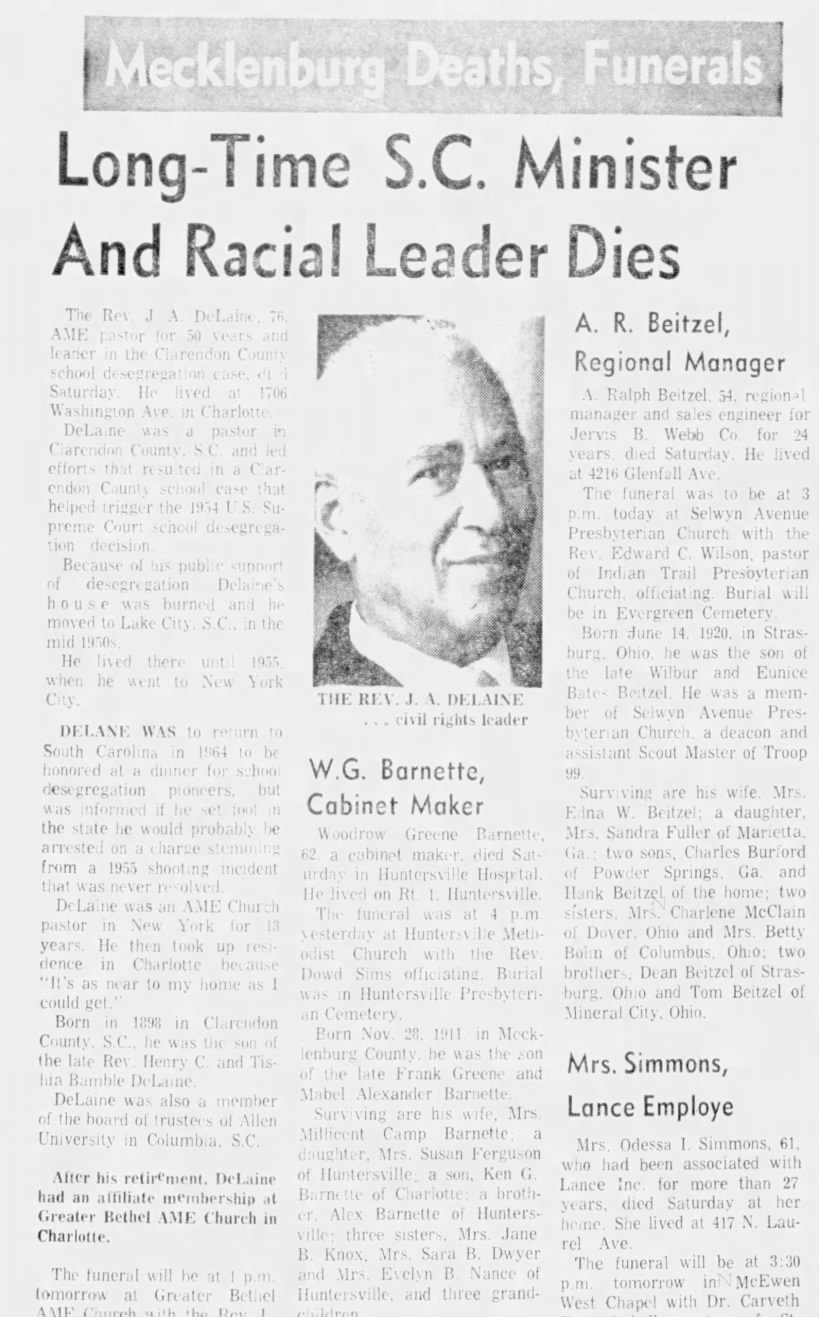

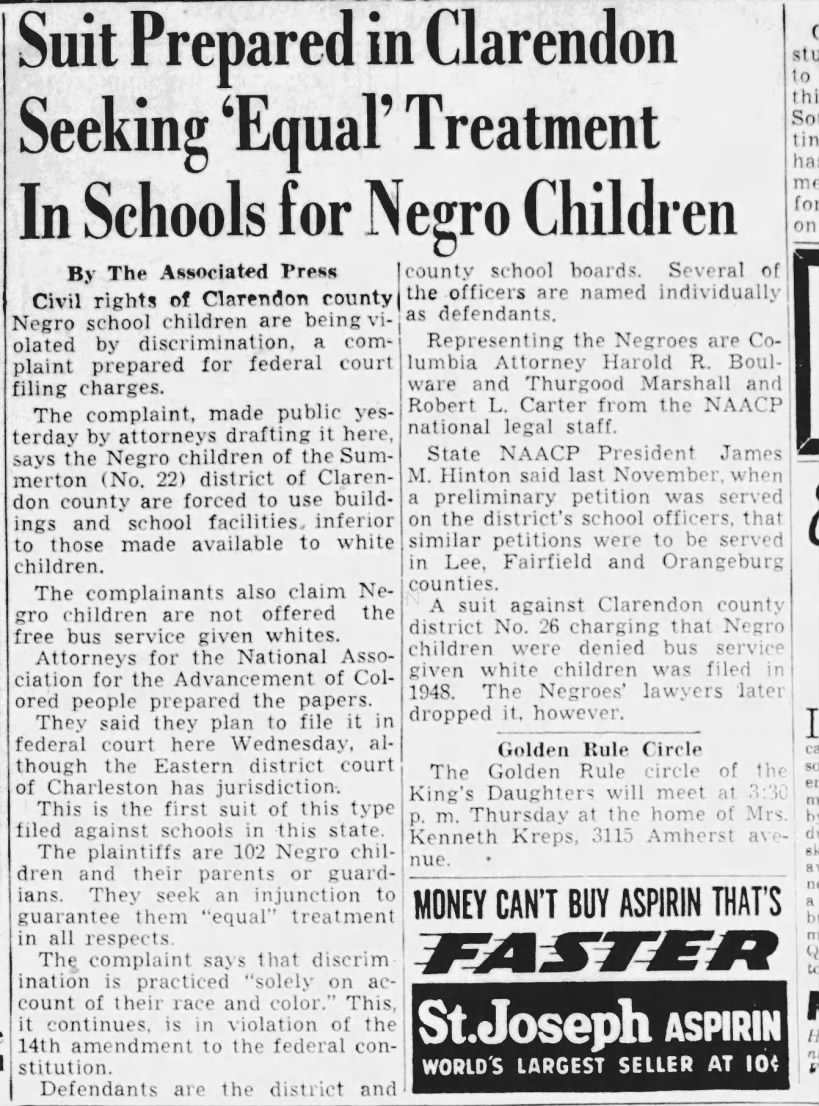

“were even adamant about keeping their names on the petition. Miss Liza and Miss Gardenia, for example, went so far as to threaten to leave Mr. Harry and Mr. Bo if they removed their names.” (Ophelia De Laine Gona, Dawn of Desegregation: J.A. De Laine and Briggs v. Elliott(Columbia, South Carolina: University of South Carolina Press, 2012), 115.)